Technology & Supply Chain In Healthcare

Preface

According to The Beryl Institute research, the patient experience is one of the top three priorities of hospital leaders over the next three years. It is clearly time to refocus on the person at the center of care. Many organizations are struggling to understand what patient-centered care truly means, and what it really looks like. Every caregiver has a role in the patient journey, from the valet attendant, to the CEO and clinical staff… Successful hospitals provide an exceptional patient experience. Organizations with a culture that focuses on patients are rewarded with higher clinical quality and efficiency, a safer patient environment, greater caregiver engagement, and improved financial results. The supply chain is a critical component of a hospitals’ success towards providing an exceptional patient experience. It hosts a vast network of products, services and players all intended to serve the patients, their family and caregivers. Managing the flow of information, supplies, equipment, and services from manufacturers to distributors to providers of care is especially difficult in clinical supply chains, compared with more technology-intense industries like consumer goods or industrial manufacturing. As supplies move downstream towards hospitals and clinics, the quality and roAdd Mediabustness of accompanying management and information systems used to manage these products deteriorates significantly. Technology that provides advanced planning, synchronization, and collaboration upstream at the large supply manufacturers and distributors rarely is used at even the world’s larger and more sophisticated hospitals. This paper outlines the current state of healthcare supply chain management technologies, addresses potential reasons for the lack of adoption of technologies and provides a roadmap for the evolution of technology for the future. This piece is based on both quantitative and qualitative research assessments of the healthcare supply chain conducted during the last two years…

Introduction

Technology to better plan and manage the acquisition and replenishment of key resources, such as pharmaceuticals, supplies and equipment, are severely lacking in hospitals today, compared with other industries. Driven by continual cost pressures and other operational constraints, the supply chain represents one of the largest opportunities for cost savings and value creation in the healthcare enterprise, but a comprehensive roadmap is needed to help assist hospitals. This white paper suggests that hospitals create an evolutionary path for supply chain technologies, implementing better business practices and more advanced technologies to increase vendor collaboration, optimize pricing and sourcing efforts, and improve the prediction of required order quantities and inventory levels. When hospital executives talk about technology, they most commonly refer to clinical decision support, medical informatics, or electronic medical records (EMR’s). A wide range of technology and systems are developing that bring advanced decision support to the forefront of healthcare practice in the “front office,” which is the point of care or place at which care is provided to patients. In the “back office,” representing the administrative and financial functions, there has been only minimal progress in implementing technology. There is continued deployment of enterprise resource systems, but these tend to focus primarily on business processes that are generally considered more visible and seen as “strategic,” such as human resources or financial management. Although most of these enterprise systems have procurement, inventory, and distribution capabilities, they are rudimentary in scope and function, providing mainly transactional and limited reporting capabilities. This limited functionality needs to be expanded to take a wider, strategic perspective on the clinical supply chain. Supply chain management (SCM) is defined as the planning, organizing, and controlling of functions inside and outside a “company” that enable the chain to make “products” and provide “services” to the “customer”. “1” All of the parties in the clinical chain ”patients, providers, materials department, vendors, distributors, and manufacturers” need to work together to create a chain that is effective, even as each entity in the chain is fighting to carve out a profit or cost saving. The focus on the entire supply chain, from suppliers through the delivery of care, is a relatively new concept in hospitals; it represents a departure from the normal materials management perspective of managing internal, discrete business functions separately. However, it represents a major opportunity for patient value enhancements, as other industries have learned over the last decade. “2” Optimizing the supply chain is important, because pharmaceutical supply and materials expenses consume approximately 35 percent of hospital expenditures in most organizations. When accounting for all supply chain expenses, including the administrative cost of procuring, receiving, and administering the chain, total expenses for this area can account for nearly 43 percent of all hospital expenses. Because hospitals have tackled a number of other automation projects with easier returns on investment, supply chains for clinics and hospitals now are primed to begin the transformation that most other consumer-based industries have undergone in the past 20 years. This area, known as supply chain technology, has yet to receive significant attention in hospitals. In the healthcare industry, SCM technology has been widely used by medical supply manufacturers and large distributors, but has yet to trickle down the chain into hospitals and to the point of care. In other industries, such as manufacturing, automotive, and retail, there has been significant deployment of supply chain management systems. However, hospitals have not significantly adopted the majority of these technologies, and they remain far behind in scope and sophistication compared with virtually every other industry. A meta-search of healthcare information systems books published in the last 5 – 8 years shows very little coverage of supply chain systems, their importance, or their future. Even when supply chain technology topics were addressed in publications, they were discussed in the generic sense, mentioning the most common functions of automating inventory control, purchasing, and receiving. Advanced texts on supply chain management and technology hardly ever mention the hospital industry in cases or context. Regardless of the current state of hospital supply chain technology, the direction is clear even though the pace of change is not. While the hospital industry has unique concerns and challenges, the basic requirements remain the same in all industries; that is the need to predict the right location, the right price, the right time, and the right products. That suggests that hospital SCM systems will evolve as they have in consumer-driven and manufacturing industries. The only unknown is the timing of when individual hospitals will begin this evolution, which will partially be based on each organization’s financial condition and the vision of their executive and operational leadership teams.

Supply Chain Technology

Consumer-driven industries have led efforts to develop and deploy enterprise systems and associated supply chain technologies. Historically, the scope of enterprise systems has focused on automating specific transactions, such as order processing and invoice generation. The initial spotlight on automation during the 1960s through the 1980s saw information technology primarily as a means to reduce costs and improve operational efficiencies. This early focus on internal activities, efficiencies, and execution resulted in some early success in minimizing costs. When enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems were first being introduced, they were seen as the way to handle large volumes of enterprise data in terms of sales transactions, materials masters, and other manufacturing and sales data required to manage the entire business. Since then, there has been a gradual shift away from execution towards planning processes. New processes and technology were developed for material requirements planning (now called manufacturing resource planning), which began the shift towards better planning of production and inventory requirements to manage logistical operations (now called supply chains). The continued evolution towards MRPII was an extension of this focus on planning. During the last decade, SCM technology began to focus on planning and effectiveness instead of execution and efficiency. Business process re-engineering and total quality management helped force a “process” view of the enterprise, and prompted companies to start looking not only at inputs but also at outputs, as well as the processes used to link the two. Advanced planning systems (APS) were the first to focus on areas such as production scheduling, demand forecasting, capacity planning, and network optimization. Customer relationship management (CRM) emerged and began to focus on capturing all customer data in one location to improve call center management, sales force automation, and marketing automation.

Now that operational and tactical processes have been addressed, SCM technology will begin to focus on what the software industry calls demand-based systems, which include predictive modeling, data mining, and business intelligence. These systems continue the evolution towards more strategic planning solutions for SCM optimization because they help focus firms on effectiveness and margin enhancement.

Clinical Supply Chains

But where are clinical supply chains in this evolution? While hospitals have focused on bringing decision support to clinical practitioners, there has been a general neglect of management systems to support supply chains. Recent research on supply chain business practices was performed by the author at several hospitals throughout the United States. The research found that fewer than 25 percent of hospitals use statistical forecasting to support inventory planning and replenishment. If forecasting was performed at all, the most common methods were using the ERP system’s auto-forecast or simple trending through conventional spreadsheet analysis. The inability to accurately forecast supply usage and convert such predictions into an automated procurement and replenishment plan results in sub-optimal, manual, and inaccurate processes. The survey also found fewer than 10 percent of hospitals are using inventory optimization techniques to manage inventory. Among surveyed hospitals, no formal collaborative forecasting, planning and replenishment projects were under way. The most cited reason for lack of tighter collaboration and integration was trust with key vendors and distributors. Collaborative processes that stretch beyond organizational boundaries are an initial step in reducing expenses throughout the entire chain. Hospitals have not widely deployed point-of-use systems for managing supplies, mainly because of capital costs and systems integration issues with supporting systems. Surveyed hospitals also indicated a high degree of interest in using radio frequency identification for managing key drugs and materials, but none of the facilities had such a system in place. The facilities exhibited a widespread redundancy in systems, especially on the patient billing side. Most hospitals use one system as their primary billing system, and use their ERP system for managing supplies and inventories, thus creating the potential for re-keying data or hard-wired integration between systems. Based on these findings, hospitals and the healthcare industry generally lag significantly behind other industries in deploying management systems to support supply chain management. Most hospitals still have the mindset of capturing transactions and have not yet made the mental leap of seeing an optimized supply chain as a tool for competitive advantage.

A Model for Hospitals

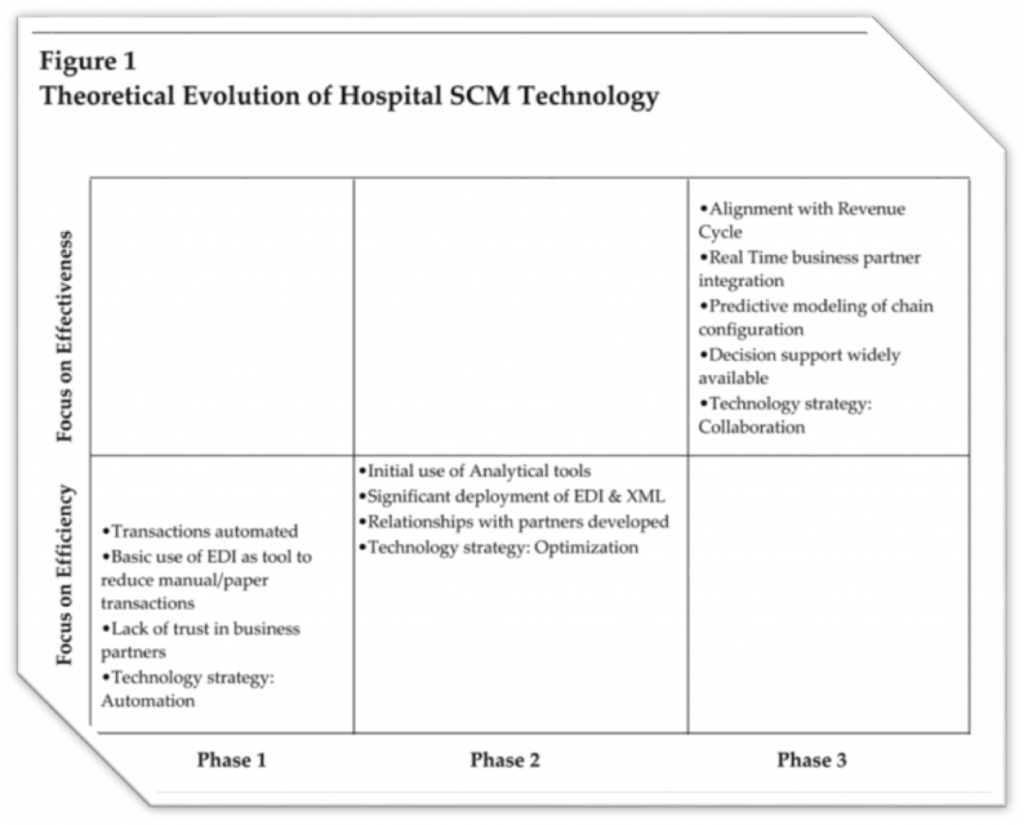

“Figure 1” shows a theoretical evolutionary model of development for hospital supply chain technology. Nearly 10 years of research into more advanced supply chains, like aviation and industrial manufacturing, suggests that hospital supply chains will move in a similar pattern. Directionally, SCM technologies will focus more on becoming strategic, enhancing planning and effectiveness (in this figure, moving up the y-axis of the model), and less on the more tactical processes of automation and efficiency. On the x-axis, hospital technology generally will move through three phases as hospitals become strategic. This three-phase approach was first discussed in literature to represent how technology is changing the world’s most successful consumer-driven value chains. Most hospitals, including the largest and most advanced hospitals, are only in Phase 1 of development on this evolutionary model. During this stage, there is a strong emphasis on automating the key business processes and transactions. Ensuring that procurement staff are using electronic requisitions and purchase orders and that electronic order entry is being used for supply requests are examples of this focus on transaction automation.

In many hospitals, paper requisitions remain the norm, but they get in the way of maturing supply chain technologies. This is a necessary step to create a transaction history, which is a requirement for organizations as they move to subsequent phases and need to rely on this information for analysis and intelligence. Also in Phase 1, hospitals will explore limited use of electronic data interchange (EDI) with key vendors or distributors. Typically, this means that of the most common EDI transaction sets, only one or two are commonly in use, such as EDI 850 for purchase orders. Additionally, there is a general lack of trust in key vendors and distributors during this early phase of development, so technology strategy is not focused on building collaboration or using electronic commerce to bridge processes. Finally, the overall technology is focused on managing and minimizing supply costs, which produces a strategy involving centralization and automation. While Phase 1 produces stable results in the supply chain, there are no stellar performers. During Phase 2, there is a significant amount of transaction history that has been captured, typically about two to three years’ worth. Hospitals that have reached this phase want to use this data in creative ways and replace manual, people-intensive processes with more intelligent system processes. Using advanced analytical systems, such as forecasting and predictive modeling, supply chains can make more intelligent replenishment decisions, can optimize inventory levels, can analyze spending patterns in key categories, and can track performance metrics in significantly greater detail. Hospitals also begin to value collaboration with key suppliers and distributors and expand the use of electronic data interchange for more than one or two transaction sets. Typically, EDI progression in Phase 2 supports several transactions, such as EDI 840 (request for quotation), EDI 843 (response to RFQ), EDI 850 (purchase order), EDI 855 (purchase order acknowledgment), EDI 856 (advanced shipment notice), EDI 870 (order status report), and EDI 810 (electronic invoice). Additionally, hospital supply chains in this phase will start to explore the use of broader e-commerce tools. The initial use of XML in collaborative planning and forecasting processes for example and Internet-enabled e-procurement and online catalogs for suppliers are ways in which hospitals will move beyond EDI towards more scalable, flexible Internet technology. Overall, the technology strategy in this phase focuses hospital management systems on optimization. As hospitals progress to Phase 3, there is a much higher concentration on collaboration and integration, both of internal business processes and with external parties in the supply chain. While supply chains tend to focus inwardly on supply costs and efficiencies in the first two phases, there is a heightened focus on alignment with the revenue cycle during this phase. Ensuring seamless integration of the supply chain and the revenue cycle is vital to obtain higher effectiveness. Tracking a supply’s history into the chain, ultimately ending at consumption or the point of use by a specific patient is important in aligning revenue and supply processes, as well as reducing system redundancies. In Phase 3, hospitals and suppliers become integrated through systematic processes and technology. For example, consider an environment in which a facility’s patient acuity or procedural case mix changes; analytics would automatically suggest different buying and replenishment plans, and key suppliers could be instantly alerted to this change. Plans are adjusted, causing fewer inventories to be held in the chain, reducing expenses and ensuring strong collaboration with all parties. While such systems seem futuristic, they are in use today in many manufacturing industries.

Technology used during this phase helps support many advanced decisions that are today seen as unpredictable. For example, a hospital will have the capability to instantly determine how many items to purchase, how and where the product should be stored, key timings in the chain, which vendor they should use, what the patient chargeable price should be, and what the overall financial margin impact will be on the chain. Most of these questions cannot be answered by most hospitals that are in the first two phases of the evolutionary process. Most of the hospitals in the U.S. today are still in Phase 1 of this model, with very few at the early stages of 2. Many have not focused their limited IT resources on the supply chain, but that will begin to change as hospitals begin to use their supply chains as a competitive tool.

HOSPITAL COMPREHENSIVE SYSTEM

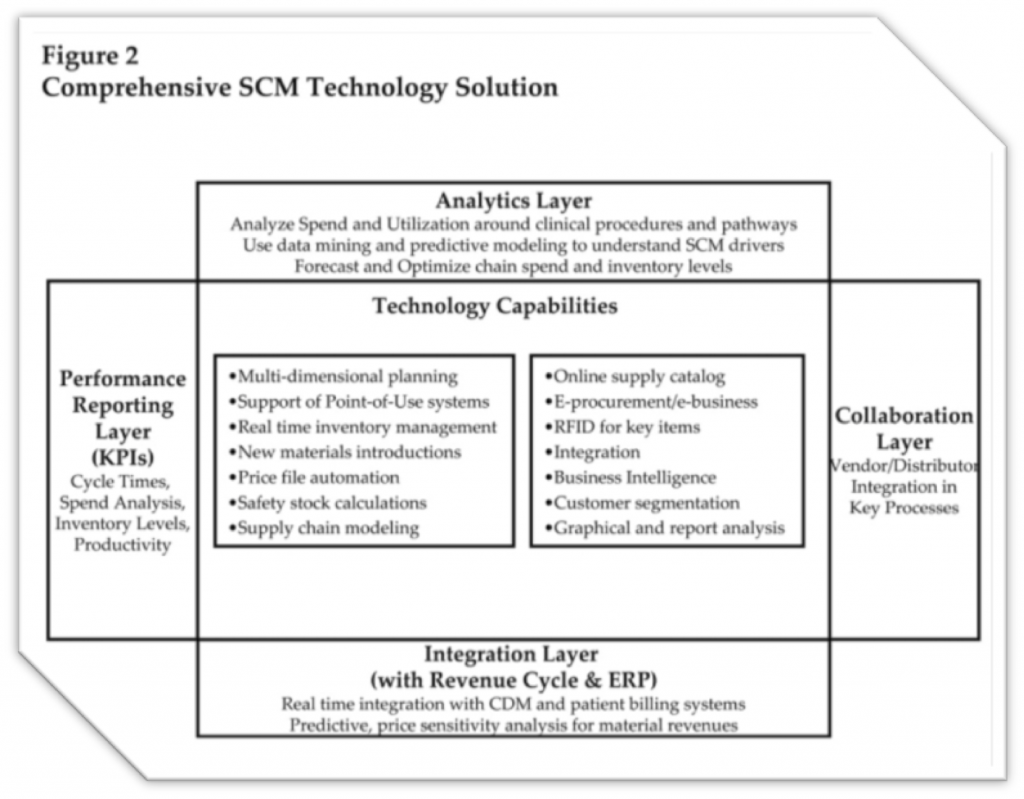

As hospitals begin to move beyond Phase 1, they will need to develop a more comprehensive SCM technology solution, with integrated systems and functionality to better support supply chains. As of today, there does not appear to be a single technology vendor that offers the functionality required in all areas of the chain to move toward Phase 3. Most integrated systems, such as ERP vendors, attempt to provide limited scope in many areas, but they do not offer rich content or sophistication in most of them. Many of the “point” solutions or niche technology vendors offer sophisticated tools, but only in one or two areas. Consequently, the optimal management system will probably be composed of several tightly integrated solutions that have key functionality in optimization and analytics, collaboration, integration, and performance reporting. Regardless, it will be up to supply chain and hospital executives to create a technology strategy to help their organizations evolve to subsequent phases. “Figure 2” shows the components of an “optimal” SCM management system. Optimal management systems will have an analytics layer that helps drive analysis into all core business processes, such as spend analysis by commodity or category; forecasting on supplies; and inventory optimization in materials storage and warehousing.

This analytics layer helps to produce real-time intelligent analyses, reducing the need for extracting large amounts of transactions, importing data into spreadsheet systems, and generating one-time analyses that are manual and time-consuming. These systems also will have a collaboration layer that supports external business processes with key suppliers, such as e-procurement, collaborative planning, forecasting, and replenishment. As the supply chain matures, collaboration with key vendors and partners will become commonplace. Similarly, these systems will have integration layers that ensure complete alignment with revenue cycle systems and processes as well as underlying ERP solutions. Integration between the charge description master and patient billing systems, and the inventory management and materials costing system, is necessary to ensure full capture of all revenues and expenses. To aid in analysis, these systems will need a performance reporting layer, supported mainly by a graphical user interface that highlights key performance metrics and, decision support. Finally, these systems must possess technology capabilities that concentrate solution functionality on each of the key areas that support optimization and collaboration. These include warehouse management, e-procurement, demand planning and forecasting, use of multidimensional planning, real-time inventory management, including RFID where appropriate on select materials and equipment, and enhanced flexibility in modeling the supply chain to meet desired results. Potential obstacles that stand in the way of the development and delivery of this integrated supply chain management system are numerous and well documented. There are literally dozens of impediments, including the lack of financial resources, lack of physician sponsorship, too many competing interests, low prioritization from IT, and lack of leadership and vision from supply chain management. However, the two most significant, yet manageable roadblocks, are trust and discipline. Trust must be broadened internally between the various functions in the hospital; more than that, trust must be engendered to share information openly with external vendors and distributors. The movement towards e-procurement and other Internet enabled processes linking multiple parties requires significant trust with key business partners. Hospital supply chain executives have historically lacked this trust. Additionally, the lack of disciplined strategic thinking in materials management has limited the deployment of SCM technology. Disparities in disciplined thought to build a technology plan, to build required business cases, to explore new technologies, and bring them into healthcare, and to take a disciplined approach to implementing and following through has contributed to the quality and robustness chasm in SCM technology that exists between hospitals and other industries.

Conclusion

Hospital financial operating margins continue to be negative or marginally positive, forcing facilities to look at all opportunities for reducing costs and enhancing revenues. As clinical supply chain management focuses on becoming more strategic and effective, the management systems must evolve substantially. Regarding the evolution of supply chains, hospitals lag significantly behind other industries in deploying advanced management systems to drive supply chain optimization. Hospitals must begin to value the supply chain as a potential tool for competitive advantage and focus on management systems in this area if they are to catch up to other industries or make progress. Also, hospitals need to shift their internal information technology strategy to focus more resources and vision on the supply chain. CIO’s and their staff must become more engaged in defining SCM business processes and performance metrics, and helping to align the SCM technology strategy and respective roadmap accordingly.

Moreover, an integrated portfolio of management systems must be deployed to achieve the vision of an optimal SCM system, because it is highly unlikely that a single vendor will be able to provide advanced functionality in each of the areas specific to the hospital industry. This integrated approach requires an organization to prioritize functionality and establish a single supply chain technology strategy, knowing which areas will add the highest value for each individual hospital. Finally, this integrated SCM system must focus on collaboration, optimization, planning, and effectiveness. Opportunities exist for significant cost reductions and revenue enhancements, just as they do in other non-healthcare industries, if they are pursued ambitiously and with vision and discipline. If executed appropriately, based on experiences from implementations in multiple industries, hospitals can expect significant improvements in performance, such as a 15 percent to 20 percent decrease in inventories, an improvement of several percentage points in revenues, a 10 percent reduction in returns, and significant declines in the cost of goods sold.

Attend a 5-Day workshop with Mohammed Al Ayoubi in Dubai:

Transforming the Patient Experience

For more information, contact PLUS Specialty Training

+971 (0) 4 556 7171 [email protected] www.meirc.com/plus

Related Blogs

Implementing AI into your organization. Where do you begin?

Starting with AI in Your Organization: Building the First Capabilities Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming the business landscape, offering unprecedented opportunities for innovation, efficiency,...

Healthier Financials from the Patient Experience

Performance on patient experience scores can impact the cash flow and operating profit margins of hospitals, which may mean organizations have to align quality metrics and leadership to influence patients’ percepti...

Healthcare Leadership Development

Healthcare is one of the largest industries in the world and those employed within it are responsible for ensuring that everyone has access to healthcare in a timely, cost-effective and seamless manner....

Turning the Credit and Collections Department into a Profit Earning Function

Below is a real-life case study by Jon Ray MICM. A few years ago, I was doing some consultancy work for one of the big European banks. This institution had some i...